Olu Oguibe

Olu Oguibe, Game

Olu Oguibe, Game

Olu Oguibe, Game (particular)

Olu Oguibe, Game (particular)

Olu Oguibe, Game (particular)

Game

My first visit to Liguria was pleasant and memorable. However, it also fell into a period of considerable anxiety and tension that ultimately ended in tragedy. While I and others celebrated the revival of the historic collaborations between contemporary artists and master ceramists in Albisola, a few miles away in the neighboring port city of Genoa an intense battle was being waged between Italian security forces guarding the annual convention of leaders of the eight leading industrial nations, or the Group of Eight, and thousands of social activists who had gathered to protest the agenda of the meeting and the rapacious propensities of globalization. The celebrations in Albisola, which marked the first Biennial of Ceramics in Contemporary Art, were described as “the happy face of globalization” because they brought together international practitioners from all parts of the world who came to work with and acknowledge the expertise and significance of a local industry in what many would now refer to as a positive demonstration of glocalization. They were referred to as the happy face of globalization in recognition of the parallel gathering in Genoa where great powers debated and decided the fate of millions of the world’s citizens who had neither representation nor power to challenge their machinations. In effect while the biennial in Albisola and the collaborations that produced it represented the positive possibilities of global and local interaction, the gathering on the other side of town represented in large part the tragic and diabolical face of contemporary existence.

That tragic dimension acquired unforgettable poignancy when midway through the world leaders’ deliberations in Genoa, a young activist named Carlo Giuliani was cut down in cold blood by security force bullets, and left lying in the street. The contrast between that incident and our celebrations was inescapable and indelible. In Albisola friendship, warmth and enthusiasm framed narratives of professional respect and mutual discovery through creative exchange, while across the bridge eight powerful strangers came to town with their retinues of guards and armored cars, and in their wake left a town in ruins, and a young man lying in a pool of his own blood. That tragic paradox stayed with me for long, and in response I wrote a short verse called the Ballad of Carlo Giuliani. I also promised myself that if I should return to Liguria as an artist, I would create a work of art that deals with the elaborate and complex machine that brought Carlo and his fellow protesters to Genoa, a machine so complex and diabolical that very few of them understood it.

The invitation to return to Liguria as an artist came thanks to the artistic directors of the biennial, but the work that I created took longer to coalesce. Indeed, not till the last moment was I able to see how appropriately the metaphors had come together to address the theme that lodged in my mind more than a year earlier. The title itself came long after I finished the work and left Liguria.

Like its subject, Game is an elaborate installation piece composed of a large, ceramic mural, and a set for a board game with a table and two chairs. In all but one respect the game appears to be chess, with sixty-four alternating back and white ceramic squares and an unusual orange diagonal. Yet, rather than the customary number of game pieces, I have made 101 terracotta figurines instead: the figurines representing neither Kings nor Queens, but the masses of people who presently crisscross the planet; immigrants, refugees, travelers, citizens, every one of them a pawn in an indeterminate, global game in which the real players and referees are opaque or invisible presences beyond the reach of the ordinary citizen. In this extraordinary game of power, money, territories and desires, unwitting masses are shoved around, used and abused, disemboweled, evacuated, cleansed, discounted as mere collateral, as necessary and unavoidable casualties. Cultures are uprooted and swept from ancestral land. Populations are displaced and offloaded in cities to roam unhinged and disoriented. Migrants battle ever-tightening borders, relentless and undeterred. And still the masses march, a multitude of pawns, like the crowds in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, undone not by death, but by civilization and progress.

On the ceramic mural there are eight figures, all men, representing the leaders of the group of eight industrialized nations. Each figure is dressed in colonial attire inspired in part by the wall panel art of the Nkanu people of the Congo and Angola (indeed the whole mural draws heavily on Nkanu panels in its general design.) In my research prior to producing the work, I looked for models of African representation of colonialism. Across the continent I found a consistent use of the motif of the colonial helmet, perhaps the most visible insignia of the District Officer who in colonial times represented all colonial authority. In the age of globalization, the received wisdom is that settler colonial presence being redundant it is replaced by remote control of information through global network systems in politics, the market, and the dispersal of humans and resources. However, very recent events in global politics provide strong evidence of the resurgence of settler colonialism. Standing guard over the rest of the world, the eight strong men of the new Empire oversee and manipulate the curious game of global usurpation and domination. Like Caesar or King Leopold, they move their forces wherever they may, occupy whatever land they choose, drive out disagreeable rulers and establish new colonial regimes and armies of occupation in their place. The helmet may be different, but the pattern has not changed. In other words, the motif and metaphor of the colonial District Officer are just as apt and palpable today as they were a century ago.

I produced the entire piece during two working sessions in the Ernan ceramic studio in Albisola, in August and October, 2002. The hundred and one terracotta figurines I made during two days of intense work in the studio in August, as well as began work on the mural. I finished the mural within a few days in October. In addition to realizing the wish to work again in clay, a medium that I have always relished and respected, and even more so to create a work that responds in some way to the experience and feelings generated during my first trip to Liguria, working in Albisola was very memorable in many other ways. I will always treasure the often tense but generous atmosphere working with Ernesto Canepa and his workshop, with Gianna, Annamaria, and Bouchaib, all master craftspeople who tolerated the encroachments on their space, gave advice freely, and worried themselves sick over the fact that I seemed to live solely on Coca Cola and work. Over summer and fall I had a wonderful experience working in Albisola and made new friends among artists I had hitherto only known by reputation. In the Studio Ernan I had a rare opportunity to work together with my friend Bili Bidjocka, an artist whom I greatly respect and whose work I have long deliberated on. On the other side of town I was welcomed into the family studio of Ceramiche San Giorgio where decades earlier Wifredo Lam had worked and there I painted a display ceramic plate while imagining myself in his place. A different generation, a different face, but thanks to the Biennial of Ceramics in Contemporary Art, the spirit remains.

All in all, working in Liguria was an enriching adventure that I recommend for any artist who desires to experience art making in all its deepest facets beyond the packaging ploys of contemporary practice.

Olu Oguibe

Angel Rogelio Oliva Lloret

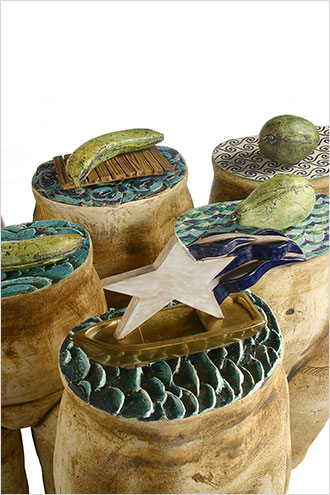

Angel Rogelio Oliva Lloret, Mare Nostrum

Angel Rogelio Oliva Lloret, Mare Nostrum (particular)

Angel Rogelio Oliva Lloret, Mare Nostrum (particular)

Mare Nostrum

The theme of the work created at Albisola is a deeply rooted yet still current part of the history of humanity: emigration. The human body is the carrier of the values of those who emigrate while at the same time acting as the receptor of new values to be assimilated. Hence everyone appears with his or her own interior ocean and a specific motivation for navigation symbolised by tropical fruits that in our culture have diverse meanings. The fish that fly rather than swim represent the constant migrations in the animal world. The paper boats evoke the primary infantile dream associated with travel that will accompany man throughout his life, a widespread phenomenon in all times and at all latitudes, hence the title: Mare Nostrum.

Angel Rogelio Oliva Lloret

Luca Pancrazzi

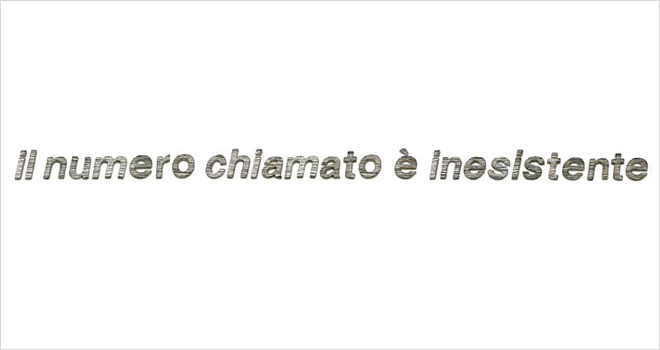

Luca Pancrazzi, Quelli che partono. La distanza è sicurezza. Quelli che restano. Il numero chiamato è inesistente

Luca Pancrazzi, Quelli che partono. La distanza è sicurezza. Quelli che restano. Il numero chiamato è inesistente

Luca Pancrazzi, Quelli che partono. La distanza è sicurezza. Quelli che restano. Il numero chiamato è inesistente

Luca Pancrazzi, Quelli che partono. La distanza è sicurezza. Quelli che restano. Il numero chiamato è inesistente

Luca Pancrazzi, Quelli che partono. La distanza è sicurezza. Quelli che restano. Il numero chiamato è inesistente

States of Mind

States of Mind. Those Who Go and Those Who Stay

A Tribute to Umberto Boccioni and Rivo Barsotti

This project involves the placing of ceramic works that together compose a tribute to Umberto Boccioni and to Rivo Barsotti in two different points. The works have been created specifically for the two sites.

While the Futurism of Ivos Pacetti encountered Albisolan ceramics , I have found no trace of Boccioni being here but his work has undoubtedly influenced me. Two paintings entitled, Those Who Go and Those Who Stay from the “States of mind” series are cited in the two installations created for the second edition of the Biennale of Ceramics in Contemporary Art.

Rivo Barsotti has left his mark on the artistic manufactures of this area and it is above all to his expert craftsmanship that I owe the realization of my first works in ceramics dedicated to the works. His name, an abbreviation of Rivoluzionario, immediately attracted me and is in turn a tribute to Futurism.

Those Who Go

There’s safety in distance

Former FFSS railway station, Vado Ligure

This virtually abandoned station is in the centre of the maritime area of Vado. Located strategically with respects to the modern expansion of the town from the beginning of the century, it is today an archaeological relic of infrastructures. The lines have been isolated since a collapse in the nearby tunnel blocked access from the west and operate solely as a goods yard for the neighbouring power station.

Today, what first catches the eye are the signs of abandonment, despite the attractive architecture and in a certain sense the state of conservation due largely to disuse: the underpass between Platforms One and Two is crumbling and allowed to flood every time it rains. Restoration work only extends to patching up, as with the glass-block skylights over Platform One, covered and walled-up rather than being repaired. Despite having lost its hands, the clock on the façade retains its function of relieving the horizontality of the structure like a wheel of time, making it movable.

The abandonment has at least allowed many features to remain intact, such as the brass and glass doors, the marble of the floors, the brass letters above the office doors and a number of window-frames and, above all, it has spared the structure from the insertion of later accessories.

Project

Two figures standing near the ticket office, dark and anonymously classical, timeless. One is turned towards the ticket office window and his minimal gestures suggest that he is discussing the route and the cost of the ticket with the seller. The other figure is behind the first and appears to be in the queue but is distracted. He/she could be the companion of the first who, respecting the privacy of the conversation, avoids approaching the window too closely. This figure has been distracted by something that has made him turn towards the glass doors of the entrance. However, an object he is holding up to his face with two hands betrays his classical timelessness; it is a modern, metallic object, possibly a video camera with which he is framing and filming those observing him. As if to offer militaristic protection to the back of the first figure, the companion notices a movement at the entrance and lines his sights on those arriving.

The second figure acts as a conductor between the actuality of the observer and the timelessness of the scene. Through the video camera the spectator’s gaze manages to penetrate the scene through to the ticket office window, seeking in the dark, reflecting surface the face of the traveller as well as that of the ticket seller on the other side.

“The journey is the traveller,” said Pessoa… “I do not go I do not stay,” said Boetti.

The platform is empty, the train has been missed or it is late.

A ceramic script, “la distanza è sicurezza” (there’s safety in distance) will be installed in a niche outside the station.

The script is composed of ceramic letters finished in a third firing with platinum enamel.

Luca Pancrazzi

Bruno Peinado

Bruno Peinado, Senza titolo. Mire Suprematiste 2

Alessandro Pessoli

Alessandro Pessoli, Untitled

Alessandro Pessoli, Untitled

Little drops

I love handling clay; you can pierce it, cut it, punch it and caress it. It’s docile but stubborn, you put it in the kiln and becomes all red, a beautiful flame red… You can colour it… and it still has to go back to be fired before emerging in its bright new skin. It then straightaway begins to stretch itself, as if in the flames it had been dreaming… making loads of little noises… squeaks… and I’m afraid that the awakening is too sudden, that it doesn’t much like the world as it is and that it’s determined to shatter into myriad fragments… just to spite me. For this reason Danilo and I have wrapped it in towels, so that it stays warm a little longer… and we’re as solicitous as one is with a newborn baby. I like ceramics because millions of hands have done it before me, and will continue to do so after me, because it’s like dipping into an ocean of gestures repeated ad infinitum, each with its weight and grace… So I feel like a little drop of water… like the water of this planet that takes on myriad forms, hides away in the darkness of the earth and floats lazily in the light but is always the same quantity as at the beginning of everything.

Alessandro Pessoli

Carla Rossi

Carla Rossi, Senza titolo

Carla Rossi, Senza titolo

Carla Rossi, Senza titolo

Hong Myung Seop

Hong Myung Seop, Para-sito

Hong Myung Seop, Para-sito

Hong Myung Seop, Para-sito

Hong Myung Seop, Para-sito

Para-parasite-site

When I thought about “Ceramics in Contemporary Art,” I was interested in the idea of the incarnation of contemporary art in the primordial firing of clay, one of the oldest cultural practices in human history.

I was deeply concerned with how I could use the encounter between water, earth, and fire in the age of contemporary image culture, and how the conventional technique of clay firing could establish a bridge between itself and the contemporary artistic situation. Could it be a temporary means to my own work?

The most important thing for me was that I would have the opportunity to create a ceramic object that I wanted to express in terms of ceramics but had always been prevented from doing so because of my lack of ceramic technique.

I have long been interested in a phenomenon which I call meta-pattern that involves similarity between totally different species. So I made a ceramic work that has the shape of an enlarged walnut kernel. Through this work I wanted to evoke the animal spirit because I saw the walnut kernel as resembling the human brain. To me, the concept of animal spirit has the same validity as the idea that plants also have spirit. Furthermore, the camouflaging of animals, plants, and human beings has the same value in the sense of cultural perspective and the ecological process.

However, I was unable to realize my idea because it was not easy to render the actual shape through my preliminary sketch alone. There was also a gap between my idea and conventional ceramic working processes. The next best way of achieving it was by using a rotating disk and by finding a method of my own.

So I set my first task as solving the conflict between the range of general ceramic products and my own idea. In general, I have been considering a problem of “site,” “here and there,” “disguised, faint site brought by parasite”. I call this “para-parasite-site.”

Through this process of thinking, I was able to find a point of contact in the seminal expansion of eggs. This also produced a dichotomized parasitical structure that I could achieve with the help of the potters. Ten egg pieces will reflect and memorize anonymous places where they will be parasites.

The surface of each work evokes landscape with visual humor, the moonlight, and the sunlight of the Albisola seashore. Egg fluid resembling sap or water will be actually fried in a kiln, thus becoming a sacrifice to the Biennale of Ceramics in Contemporary Art.

Hong Myung Seop

Shimabuku

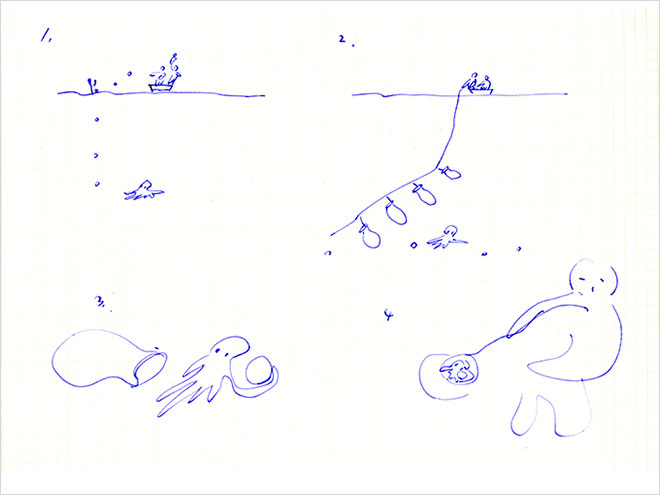

Shimabuku, Catching Octopus with self-made ceramics

Shimabuku, Catching Octopus with self-made ceramics

Shimabuku, Catching Octopus with self-made ceramics

Shimabuku, Catching Octopus with self-made ceramics

Catching octopus

I really felt at home in Albisola, because it had the sea, mountains and octopuses just like my hometown of Kobe! I was so surprised to see octopus dishes in the hotel restaurant!

I started to wonder how people in Albisola catch the octopus. In my hometown, people catch octopuses using ceramic pots. They simply string many pots on a long rope and let them sink to the bottom of the sea. No bait is used. When the trap is retrieved in 24 to 48 hours, the octopuses are found inside the pots. This method takes advantage of the fact that octopuses like narrow spaces. Danilo, my ceramics craftsman told me that Italian people used to use a similar method a long, long time ago.

Danilo and I decided to do things the ancient Italian and my hometown’s way and catch octopus in present-day Albisola using self-made ceramic pots.

Shimabuku

Nedko Solakov

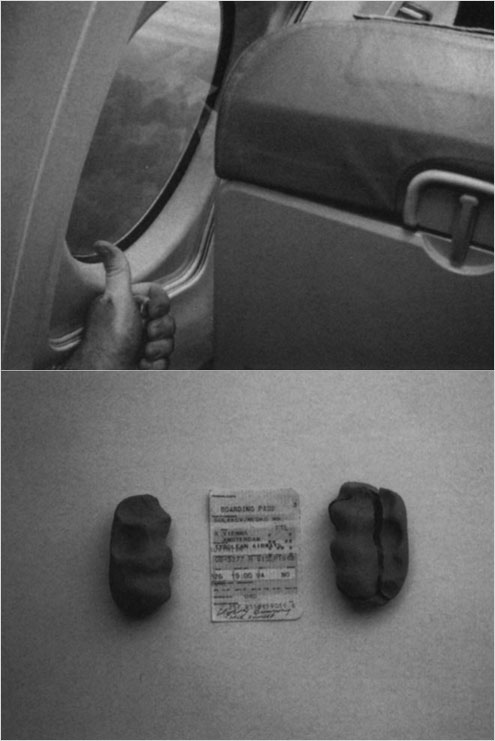

Nedko Solakov, Fear

Nedko Solakov, Fear 1

Nedko Solakov, Fear 2

Nedko Solakov, Fear 3

Nedko Solakov, Fear 4

Nedko Solakov, Fear 5

Nedko Solakov, Fear 6

Nedko Solakov, Fear 7

Nedko Solakov, Fear 8

Nedko Solakov, Fear 9

Nedko Solakov, Fear 10

Fear

I am scared of flying. Really scared. And, for the time being, I have to fly all the time.

Before every departure I take a pill. Sometimes, if it is an overseas flight, I take two. Naturally, this is not enough to block my fear. While I am on board, I constantly pray my own words in a kind of a very personal mantra. That is not enough either. Most of the time, almost all the time, I keep my fists tight with thumbs up for good luck. I touch the plane with them too. For good luck.

When I was invited to create a ceramic sculpture for the Biennale of Ceramics in Contemporary Art, I was not quite sure if should I accept. But then one day, while airborne on my way to the next exhibition, with my fiercely and painfully squeezed fists, I realised what would possibly make me interested in doing something with that overtly classical material — the clay.

I asked the organizers and they sent me some balls of the finest Albisola clay.

Between July 3rd and September 15th, 2002, I carried small balls of clay in my hands during all the flights I took to various destinations. To transform these balls into works of art was very easy. I just exploited my natural (and acquired) fear of flying and kept squeezing them all the time in my fists. Some of them were held for three hours, some for one. The sophisticated material captured the nervous convulsions of my terrified hands, triggered by all that bumping, babies crying and the moments of relatively quite cruising (which are the worst because I expect something — For God’s sake No! — to happen every minute). I stopped the Fear series when I was supposed to repeat a flight, which happened to be Sofia-Munich. Meanwhile, while visiting Albisola, I left the first three pairs of Fear sculptures to be fired by a professional ceramicist. The other seven pairs remained in my Sofia studio for several months to dry.

Needless to say, I have other fears too. One of them manifested itself with the very specific concern that if I was going to send the raw clay sculptures to Italy by courier they might have been damaged. So, I decided to fire them in Bulgaria and to ship them safely later as more robust fired terracotta pieces. However, my knowledge with regards to the firing of ceramics is pretty vague. After asking around for a reliable kiln, I finally decided to use the rather unprofessional kiln in which my father bakes his own extremely beautiful little abstract sculptures. He was happy to help me. Even though he was unfamiliar with that particular clay, he suggested that we should proceed as he normally does and bake the figures at a low temperature in my mother’s kitchen oven until all the moisture had evaporated and then fire them in a proper kiln that reaches high temperatures fairly quickly. No, I said, my Fear sculptures are dry enough; they have been drying for seven months. Perhaps I should mention that despite my cautiousness and doubts about everything, I do really stupid things as well. Although my father was not convinced, I pulled rank as the more famous artist of the two of us.

The laws of nature naturally made themselves felt. After twenty minutes of firing, my extremely anxious father entered the sitting room and said that there were booming sounds coming from the kiln in his studio. We switched it off and after opening the door a devastating sight appeared before our eyes. All of the Fear sculptures, the testaments to my panic up there 10.000 meters above the ground, came out in pieces, some bigger some smaller. Another fear then took over. My parents (both with serious heart conditions) were getting extremely worried. I had to make up something and to assure them that I would be able to handle the situation. The famous Bulgarian proverb “Out of bad can come good” came to mind and I convinced them that my sculptures were now looking much better and the concept was all the more profound. Luckily, the second batch of clay sculptures that was supposed to be next in the little kiln was undamaged, so my father baked it (along with the broken pieces of the first set) in his way and everything worked out fine, of course.

What you see now, my dear viewer, is a combination of unbroken and broken Fear sculptures. All the tiny fragments you see really belong to this or that particular piece. I spent many hours restoring their shapes. Because of my stupidity, my original idea was destroyed although all the baked clay here, no matter in how many pieces it now appears, was with me in those ten aircraft and I believe that all of them do carry elements of my fear on those ten flights.

I am superstitious too. The overwhelming thought in my mind now is this — if these so carefully prepared little Fear sculptures are partly broken, what about me and the future flights that I am supposed to take? What I am supposed to hold and squeeze now, while I am still on the ground, to try to overcome the newly born fear deriving from these broken Fear sculptures? Should I fly at all from now on?

Nedko Solakov

›› More Project - page: 1 2 3 4 5 6